In Introduction to HF – Part 1, we covered the HF bands, their properties and what you could expect to hear on them. In this second part, we look at transceivers and include a few suggestions for those both new and second-hand. Some of the more advanced/useful features are also covered such as IF-Shift, VFO-Split and DSP Filtering.

New or Second-Hand?

There are plenty of radios to be found on eBay, Ham Forums or perhaps via your local Club – Your first radio need not be the most expensive offering from one of the big manufacturers, and with an entry-level HF radio costing in the region of £650, it’s a big commitment for the first-timer… The most expensive radios offer a range of features: digital filtering, dual-VFOs, dual-receivers, visual band-scope/waterfall etc. All these extra features can help you make a QSO: whether it’s to filter-out a nearby signal or fine-tune using the Clarifier, often, getting a QSO can simply be down to luck and not a £5000 radio….

DSP and Filtering

All transceivers have a volume control, most have a squelch knob (useful on FM), and some have an RF Gain option which lets you reduce the sensitivity of the receiver when faced with a very strong/local signal. The more modern/advanced/expensive the radio, the more advanced the features are. Modern transceivers usually offer some form of Digital Signal Processing (DSP) which can tailor the sound of the signal either on an IF (Intermediate Frequency) or AF (Audio Frequency) basis.

AF, the most common, is typically employed on radios such as Yaesu’s FT-857D and FT-897D – In both CW and SSB modes, the width of the signal can be adjusted so that unwanted “side-splatter” can be attenuated. As this is AF-based, the receiver can still be overloaded by strong adjacent signals. This is because the AF-based DSP is, essentially, a fancy form of equalisation (just like on your Hi-Fi).

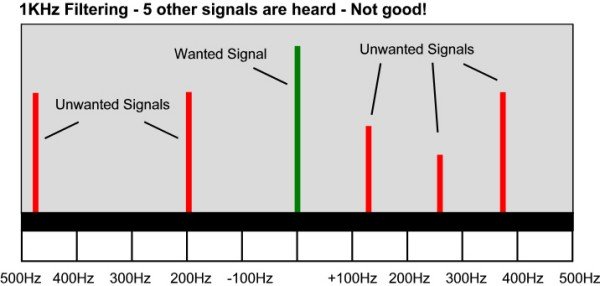

IF-based filtering, either with a more advanced radio like the FT-450D, FT-950, IC-7000, IC7100, TS-590S or an optional plug-in filter can dramatically improve the radio’s tolerance to strong adjacent signals. This kind of filtering is preferred because it is applied at the “front-end” of the receiver, allowing only the wanted signal to pass through to your speaker. The following diagram shows several signals spread across 1KHz – Let’s assume that these are all CW signals and we are only interested in the centre signal:

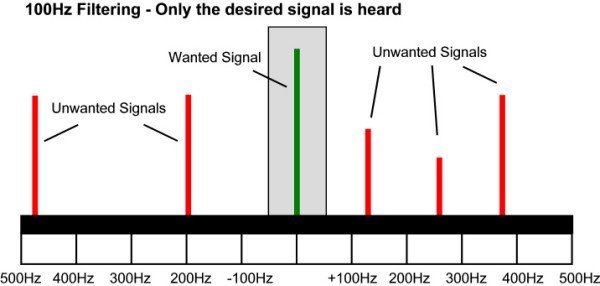

With the radio’s pass-band set to around 1000Hz, a total of 6 signals are currently being heard and it would be very hard to pick-out what’s being sent by the green (wanted) signal. So, by using a filter we can reduce the width of the receiver’s pass-band to a very small amount, in this case: 100Hz:

The radio is now concentrating solely on the signal we are interested in – The others are now inaudible (or significantly attenuated). With a narrow filter like this, it’s possible to listen to a very weak signal despite the presence of strong signals nearby. Something to think about is that a typical bandwidth on receive with a “standard” radio is as much as 2.5KHz – This is fine for SSB work, but if you want to use CW or PSK with a basic radio, you may have trouble picking-out the weaker (and usually more interesting) signals. That isn’t to say that a cheap radio is a non-starter for CW/PSK, just that you may struggle under crowded conditions – Think of it as trying to have a conversation with somebody 10ft away but with 20 other people all in the room talking loudly… quite tricky!

IF-Shift

This is another useful feature when combined with the narrow filtering described above – By adjustment the Intermediate Frequency, we can move around the centre frequency to find other signals. This is especially useful with CW but mostly PSK/RTTY digimodes. By moving the IF-Shift down, you can then focus your narrow filtering onto another signal “somewhere on the waterfall”…

VFO-Split

If you’ve listened on the HF bands and heard a station say “listening 5 up” then that’s know as “Split Operating”. A similar concept is used on 2m+70cm with a repeater: You transmit on 1 frequency, but receive on another. On HF, this practice is usually reserved for DX’peditions (to far-away and wanted Countries) but is used by Special-Event stations as well. The idea behind listening on another frequency is that the station can pick out a callsign and then give them a signal report on their clear “transmit” frequency. This allows for a more efficient series of QSOs because it doesn’t rely on the single (simplex) frequency being clear before both stations can hear each other.

To operate split, you would most likely use your radio’s VFO-B to tune 1-10KHz up (or wherever they are listening) and then transmit on that frequency. If the station says they are listening “5 to 10 up” then that means you either get heard by pot-luck or use this simple trick: Switch to monitor your TX frequency and tune around to try and hear the person they are working, that is where they are listening at that time. When they call “CQ” or “QRZ” again, you can pounce and hopefully they’ll be able to hear you. This trick works very well on CW.

Radio Ideas

A new radio may not only be a considerable investment but also quite daunting in terms of buttons, controls and menus… All modern radios are what’s know as “menu-driven”, and the smaller/simpler the radio and more emphasis is placed on menus. This is true with radios like the FT-817 and FT-857 that only have A/B/C buttons on the front, so you have to cycle through a series of “pages” to get them to activate the feature you’re interested in. By contrast, a “homebase” radio like the FT-950 or TS-590 most-likely has a dedicated front-panel button so changing functions is merely a single button press.

Powering the radio is usually via a 13.8v power-supply, although some older radios have an internal PSU and can plug directly into the mains. A switch-mode PSU can be beneficial due to their small size and capacity over a traditional “heavy transformer” power-supply. A 100-watt transceiver typically requires 22amps at full power, and many SM-PSUs from the radio dealers are rated at 25-amps. Obviously, with only 10w/50w on the Foundation/Intermediate licences, the current-draw will be significantly less. Expect to pay between £65-100 for a respectable SM-PSU.

The following radios are mentioned here as good starting points for getting onto HF – They all have their merits, and if you’re able to try before buying, so much the better!

| Yaesu FT-450D: HF and 50MHz.A compact transceiver with a range of IF-based DSP. 100-watt RF output and an easy-to-use front-panel. For around £600 you get a very good HF radio that works great on CW, SSB or digimodes. It’s small enough to hide in the corner of a room, and even take out portable.

Price new is £550-650, S/H: around £400-500 |

|

| Yaesu FT-857D: HF, 50MHz, 144MHz, 432MHz.A radio like this (HF to 70cm) is known as a “Shack-in-a-Box” as it covers most of the Ham bands. It’s a mobile-sized radio with a removable front-panel so works great in a vehicle but can also be used in the Shack or taken out portable. It offers 100w on HF+6m with 50w on 2m and 20w on 70cm. The standard DSP offered on this radio is AF-based but, like the FT-817ND, it can be upgraded with CW+SSB filters to improve selectivity at the front-end.

Price new is £680, S/H: around £500-600. |

|

| Yaesu FT-817ND: HF, 50MHz, 144MHz, 432MHz.A great QRP (low-power) radio offering all the HF bands, plus 6m, 2m and 70cm. You get 0.5w, 1w, 2.5w and 5w output on all bands as well as an internal batter-holder giving you a fantastic portable station. There is no DSP in this radio, but you can add narrow CW+SSB filters (about £100 each) to improve the performance – The 500Hz CW filter is switched in/out via a menu and also works on digimodes.

Price new is £525, S/H: around £350-400. |

|

Here are some older radios that can often be found on eBay or in the Second-hand cabinet of your local radio emporium:

- Icom IC-706: HF, 50MHz, 144MHz, 432MHz. A small “Shack-in-a-Box” that was released in several flavours: Mk1, Mk2 and Mk2G. The Mk1 saw just 10w on 2m and did not feature 70cm. The Mk2 improved the 2m power-output to 20w, whilst the MK2 added 70cm with 20w. S/H cost around £300-400 depending upon model.

- Icom IC-703: HF and 50MHz. A 10-watt radio that is essentially a IC-706 but with less power and omits 2m+70cm. Great for /P and basic HF. S/H cost around £300

Of course, you don’t have to go out and buy the latest+greatest black-box radio – You could make one! QRP kits for CW and SSB are available at reasonable prices: The MFJ-9340K is just £102 and a great little CW kit for 40m. Also take a look at CRKits , YouKits and QRPKits.com

Thanks to Charlie Davy, M0PZT for the second part of this introduction.

Read Part 3: Introduction to HF – Part 3: Aerials

For more words from Charlie, and details of his amateur radio software, go to www.m0pzt.com, or follow him on Twitter @M0PZT

“Of course, you don’t have to go out and buy the latest+greatest black-box radio – You could make one! QRP kits for CW and SSB are available at reasonable prices: The MFJ-9340K is just £102 and a great little CW kit for 40m. Also take a look at CRKits , YouKits and QRPKits.com”

I didn’t think Foundation license holders were allowed to use homebrew equipment?

Good point, I thought that as well

Foundation can build equipment but it has to be a kit or approved/proven design, they’re not allowed to put their own designs “on-air”

I wonder what vintage radios could you recommend? I am thinking about radios from ’60s and ’70s that not have micro chips and could survive EMP attack. I am just starting and when I see 100s buttons and menus on modern radios it’s overwhelming and perhaps not need to have fun with this hobby.